For more than a decade, DevOps has shaped how modern software organizations build, ship, and operate systems. It reduced silos, accelerated feedback loops, and pushed ownership closer to development teams. For many companies, it became the default model for scaling engineering. In 2026, that model is starting to show clear limits.

As organizations grow, DevOps practices that once enabled speed often introduce friction instead. Toolchains expand organically rather than intentionally. Pipelines become difficult to change without risk. Operational knowledge concentrates in a small group of senior engineers, who quietly turn into escalation points for deployments, incidents, and architectural decisions. What once felt like autonomy slowly becomes coordination overhead.

This does not mean DevOps failed. In fact, much of what still works today is rooted in DevOps principles that remain sound. But as explored in the Complete Guide to DevOps in 2025: History, Practices and Opportunities, DevOps was designed for a different stage of organizational maturity. It assumes a level of shared context and manageable complexity that becomes harder to maintain as teams, services, and constraints multiply.

At scale, engineering leaders face a new set of problems. They want teams to move independently, but without fragmenting delivery. They want standards, but without slowing innovation. They want reliability and security built in, not enforced through manual processes or tribal knowledge. These are not tooling problems. They are structural ones.

This is why internal developer platforms are gaining traction across growing engineering organizations. They represent a shift from assembling infrastructure reactively to designing it intentionally. Instead of expecting every team to navigate the same complexity, platforms provide clear interfaces, paved paths, and defaults that make the right way the easiest way.

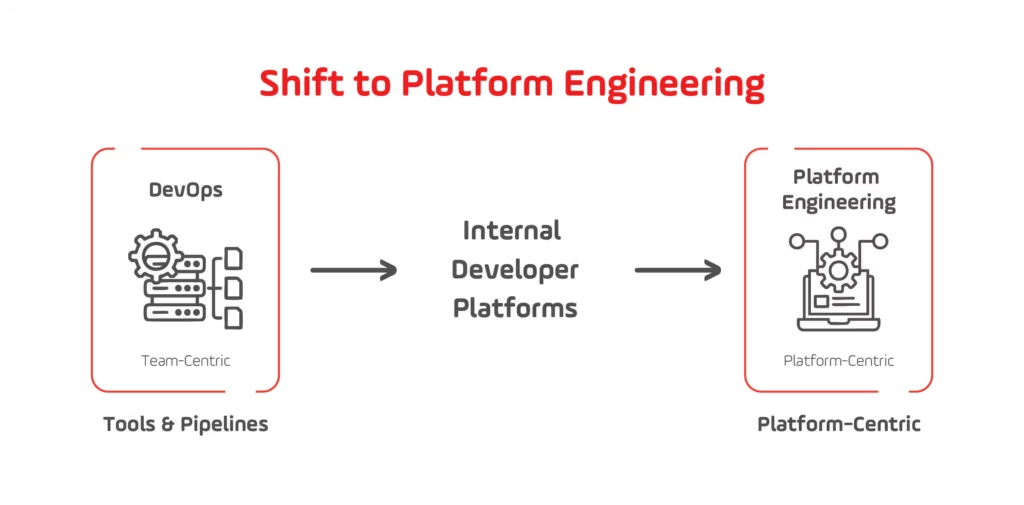

Platform engineering sits at the center of this shift. Not as a replacement for DevOps values, but as an operating model that makes them sustainable as complexity increases. Platform engineering formalizes enablement, reduces cognitive load, and creates a clearer contract between teams and the systems they depend on.

In the sections that follow, we’ll examine the five structural shifts driving the rise of internal developer platforms in 2026, and why more organizations are reorganizing around platform-led models to regain clarity, control, and momentum as they scale.

From DevOps Culture to Platform-as-a-Product

DevOps emerged as a cultural response to rigid handoffs and slow delivery. By encouraging collaboration, shared responsibility, and automation, it helped teams move faster and feel more ownership over what they shipped. For a long time, that cultural shift was enough to drive meaningful improvements. At scale, culture alone stops being sufficient.

As organizations grow, shared responsibility becomes harder to operationalize. Teams diverge in tooling, pipelines, and conventions. Knowledge that was once implicit becomes fragmented. The same DevOps principles that empowered teams early on start producing inconsistency, duplication, and hidden dependencies. This is where platform engineering begins to appear, not as a trend, but as a response to structural limits.

Why DevOps Culture Breaks Down at Scale

DevOps assumes a high level of shared context. When teams are small, that context travels easily through informal communication. As the number of services, engineers, and environments increases, that assumption no longer holds.

Teams still want autonomy, but autonomy without shared abstractions leads to fragmentation. Each team makes locally rational decisions that collectively increase operational complexity. Over time, delivery slows not because teams lack skill, but because coordination becomes expensive.

This breakdown is rarely visible at first. It shows up gradually, through longer onboarding times, brittle pipelines, and increasing reliance on a few senior engineers to “know how things really work.”

Platform-as-a-Product Changes the Unit of Design

Platform engineering reframes the problem by changing what is being designed. Instead of asking every team to assemble infrastructure and delivery workflows independently, it treats those capabilities as a product with users, requirements, and a lifecycle.

In this model, internal platforms are designed intentionally, with clear interfaces and supported paths. Teams consume them the same way they would any other product: through documentation, APIs, and self-service workflows. This reduces cognitive load and removes the need for constant coordination.

This approach aligns with organizational design ideas such as those described in Team Topologies, where reducing cognitive load and clarifying team boundaries is seen as essential for sustainable delivery.

Enablement Over Enablement-by-Heroics

One of the most important shifts at scale is how enablement actually happens. In many DevOps setups, enablement depends heavily on people rather than systems. Teams rely on informal support, tribal knowledge, and the availability of a few experienced engineers to unblock progress. As complexity grows, this model becomes fragile.

When enablement lives in individuals, it does not scale. Knowledge is hard to transfer, onboarding slows down, and operational decisions become inconsistent. Teams may appear autonomous, but that autonomy is often conditional on access to the right people at the right time.

Platform engineering changes this dynamic by moving enablement into the platform itself. Guardrails, defaults, and paved paths encode best practices so teams no longer need to rediscover them through trial and error. The result is not less autonomy, but more dependable autonomy, where teams can move independently without increasing operational risk.

This shift closely mirrors how modern automation practices reduce manual coordination and hidden dependencies. As described in CI/CD Pipeline Automation: A Complete Beginner-to-Expert Guide for Modern DevOps, sustainable scale comes from embedding best practices into systems rather than relying on individual expertise.

From Cultural Alignment to Structural Design

DevOps culture remains important, but culture cannot compensate for poorly designed systems at scale. Platform engineering builds on DevOps values while acknowledging that scaling organizations require explicit structure.

By treating infrastructure and delivery capabilities as a product, organizations move from relying on shared understanding to designing for repeatability. This marks the point where teams stop scaling through effort and start scaling through design.

The Rise of Internal Developer Platforms

As organizations grow beyond the limits of informal DevOps practices, a recurring tension appears. Engineering teams want autonomy to move quickly and independently, while leadership needs consistency, reliability, and visibility across an increasingly complex landscape. Internal developer platforms have emerged precisely at this intersection.

Rather than asking every team to assemble infrastructure, pipelines, and operational workflows from scratch, internal developer platforms provide a shared foundation. They centralize common capabilities and expose them through self-service interfaces that teams can use without deep infrastructure expertise. The objective is not rigid standardization, but repeatability where it matters most.

This shift is increasingly visible across large engineering organizations. In 2025, platform-centric approaches are being adopted not as experimental initiatives, but as part of long-term delivery strategy, particularly in environments where scale, compliance, and reliability are non-negotiable. As outlined in The strategic importance of platform engineering in modern software development, internal platforms are becoming a structural response to complexity, not a tooling trend.

Why Internal Developer Platforms Emerge at Scale

Internal developer platforms rarely appear in early-stage teams. When organizations are small, shared context and direct communication allow informal practices to work. As teams multiply, systems diversify, and constraints increase, that shared understanding erodes.

At this stage, teams still want autonomy, but autonomy without shared abstractions leads to fragmentation. Each team solves similar problems in slightly different ways, increasing cognitive load and operational risk. The result is slower onboarding, inconsistent delivery practices, and greater dependence on individual expertise.

Internal developer platforms respond to this repetition by consolidating common workflows and infrastructure patterns. Instead of scaling through documentation and best intentions, organizations scale through systems that encode standards and best practices by default.

Self-Service Without Losing Control

Self-service is often misunderstood as removing constraints. In practice, effective self-service depends on well-designed boundaries. Internal developer platforms provide opinionated paths that balance speed with safety.

Teams can provision resources, deploy services, and observe systems through predefined interfaces, while platform teams retain governance and visibility. This reduces friction without sacrificing operational discipline, and it significantly lowers the cognitive burden on individual teams.

This approach mirrors lessons learned in modern DevOps environments, where delivery speed increasingly depends on reducing manual coordination and hidden dependencies, rather than adding more tools.

Internal Platforms as an Expression of Organizational Design

Internal developer platforms are not neutral technical artifacts. They reflect organizational choices about ownership, responsibility, and collaboration. What the platform makes easy, and what it deliberately constrains, signals what the organization values.

For this reason, internal developer platforms are closely tied to platform engineering as an operating model. They are the concrete manifestation of treating enablement as a product and scaling concern, rather than a side effect of tooling decisions.

From Shared Tools to Shared Capabilities

The rise of internal developer platforms marks a shift from sharing tools to sharing capabilities. Instead of relying on documentation and individual expertise, organizations rely on platforms that guide teams toward good outcomes by design.

This shift prepares the ground for clearer distinctions between platform teams and product teams, and it sets up the operating model transition explored in the next section.

Platform Engineering as the Operating Model Behind Internal Platforms

Internal developer platforms do not exist in isolation. They are the visible outcome of a deeper organizational decision about how enablement, ownership, and responsibility are structured. That decision is what platform engineering formalizes.

At its core, platform engineering is not a role, a team name, or a tooling layer. It is an operating model that defines how shared capabilities are built, maintained, and consumed across an engineering organization. Where DevOps emphasized cultural alignment and shared responsibility, platform engineering introduces explicit structure to make that alignment sustainable at scale.

This distinction matters because many organizations attempt to build internal platforms without changing how decisions are made or who owns long-term outcomes. The result is often a collection of well-intentioned tools that struggle with adoption and clarity.

From Shared Responsibility to Explicit Ownership

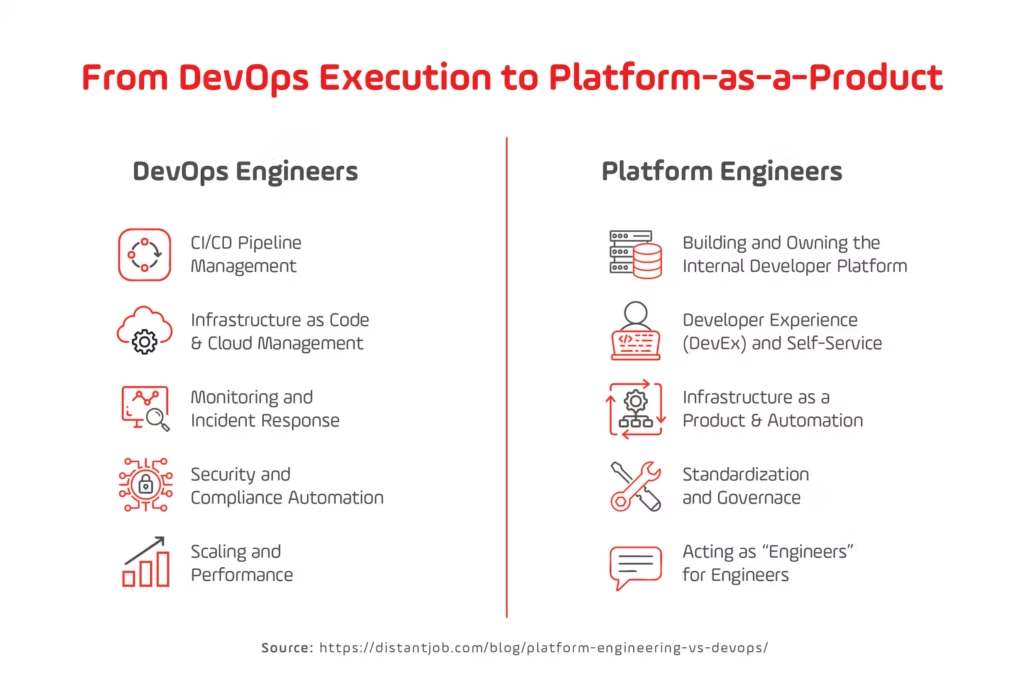

One of the defining characteristics of platform engineering is explicit ownership. Platform teams are accountable for the lifecycle of the platform in the same way product teams are accountable for customer-facing systems. This includes reliability, usability, documentation, and evolution over time.

This shift addresses a recurring DevOps failure mode: when everyone owns something, no one truly does. As systems grow more complex, implicit ownership becomes a liability. Platform engineering replaces that ambiguity with clear boundaries and interfaces, without reverting to rigid handoffs.

This mirrors patterns already observed in mature DevOps environments, where scaling success depends less on tooling choices and more on how responsibilities are distributed. These dynamics are also reflected in discussions around DevOps maturity and scalability, such as those explored in DevOps KPIs That Matter: 7 Metrics You Should Be Tracking, where ownership and feedback loops become central performance drivers.

Platform Teams as Engineers for Engineers

Platform engineering also reframes who the “user” is. Platform teams do not build for abstract infrastructure goals; they build for developers. Their success is measured by adoption, ease of use, and the ability to remove friction from everyday delivery work.

This is where the operating model becomes visible in practice. Platform teams design paved paths, defaults, and abstractions that guide teams toward good outcomes without forcing them. Product teams retain autonomy, but that autonomy is supported by systems rather than informal agreements.

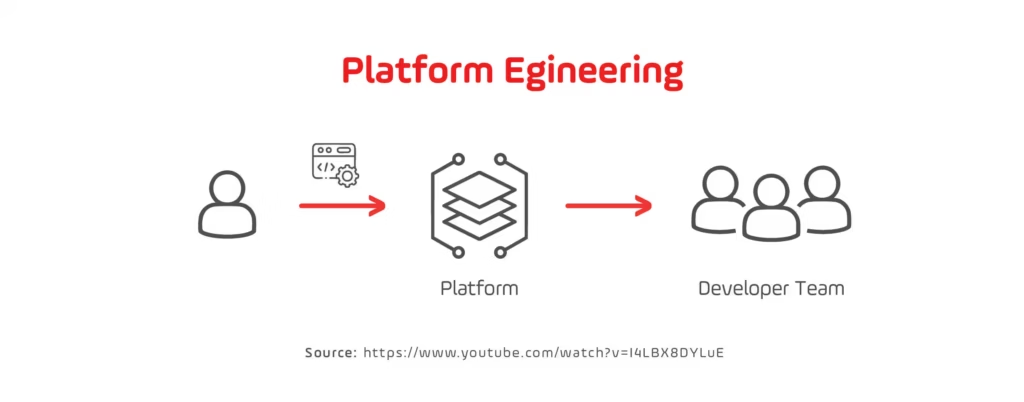

At this point in the narrative, the platform engineering model can be understood as a mediating layer between organizational intent and day-to-day execution — which is exactly what the visual you selected illustrates. The platform sits between teams and delivery, absorbing complexity so it does not have to be solved repeatedly.

Governance by Design, Not by Exception

Another defining aspect of platform engineering as an operating model is how governance is applied. Instead of relying on reviews, approvals, or manual enforcement, governance is embedded into the platform itself.

Security, compliance, and reliability requirements are encoded into workflows and defaults. Teams do not need to remember policies or interpret documentation; the platform guides them toward compliant behavior by design. This reduces friction while increasing consistency — a balance that becomes critical as organizations scale.

This approach aligns closely with architectural patterns that favor decoupling and clear boundaries, such as those described in Event Driven Architecture Done Right: How to Scale Systems with Quality in 2025, where systems are designed to scale through structure rather than coordination.

Why Platform Engineering Becomes Inevitable

As organizations grow, the choice is rarely between platform engineering and no platform engineering. It is between intentional design and accidental complexity.

Platform engineering emerges when organizations recognize that scaling through effort does not work indefinitely. By treating enablement as a product and an operating concern, platform engineering provides a way to preserve speed, autonomy, and reliability without relying on heroics.

This is why platform engineering sits at the center of modern internal developer platforms. It is the model that makes them viable over time.

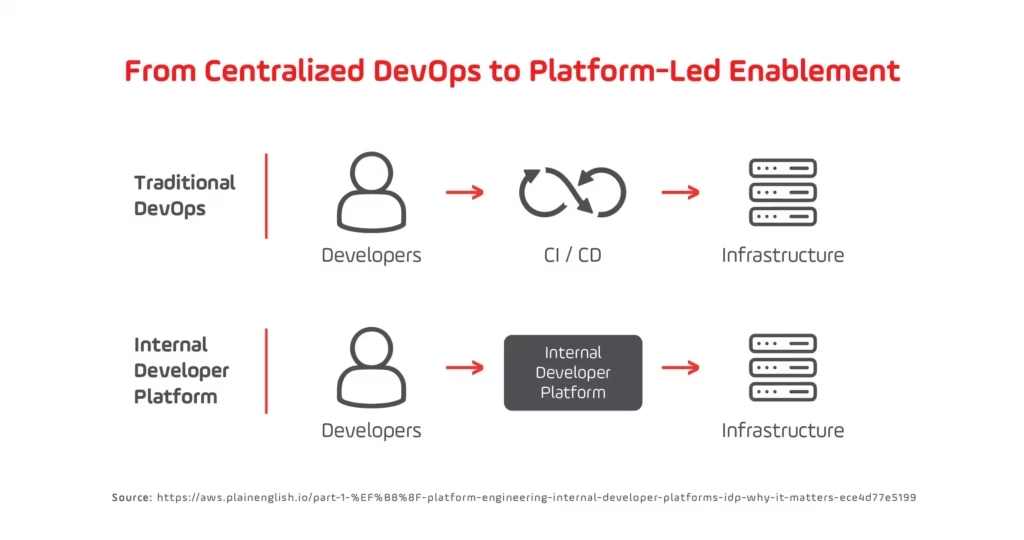

Platform Teams Replace Centralized DevOps Teams

As organizations scale, the limitations of centralized DevOps teams become increasingly visible. What often begins as a way to standardize tooling and share expertise gradually turns into a bottleneck. A small group becomes responsible for pipelines, infrastructure changes, security controls, and operational support across many teams. At that point, DevOps teams stop enabling delivery and start absorbing friction.

This is not a failure of people or intent. It is a structural issue. Centralized DevOps teams are asked to balance competing priorities across products, environments, and business constraints. As demand grows, responsiveness drops. Informal workarounds appear. Delivery slows in subtle but persistent ways.

Why Centralized DevOps Becomes a Bottleneck

Centralized DevOps models struggle because they concentrate responsibility while demand continues to grow. Every request adds context switching. Every exception increases cognitive load. Over time, teams begin to wait rather than ship.

This pattern is increasingly visible across the industry. In 2025, broader cloud and DevOps trend analyses point to a shift away from centralized execution models toward platform-led approaches that scale through enablement rather than coordination.

The issue is not tooling maturity. It is that centralized teams cannot scale linearly with the number of product teams, services, and delivery paths they are expected to support.

Platform Teams Change the Shape of Enablement

Platform teams address this problem by changing how enablement works. Instead of acting as an execution layer for other teams, they focus on building and maintaining shared capabilities that product teams can consume directly.

This changes the interaction model. Product teams no longer submit tickets for infrastructure changes or pipeline updates. They interact with platforms that already encode those capabilities. The platform team’s work scales because it is reused continuously without additional coordination. Enablement shifts from reactive support to intentional design.

Clear Interfaces Replace Informal Coordination

One of the most important consequences of this shift is the introduction of clear interfaces. Platform teams define what they provide and how it is consumed. Product teams understand the boundaries and expectations without relying on undocumented conventions or personal relationships.

This clarity reduces friction across the organization. Teams move faster not by bypassing controls, but because controls are embedded into the platform itself.

As platform engineering adoption has increased, many of the early misconceptions around control and ownership have begun to fade. Recent industry discussions highlight how platform teams are increasingly understood as enablers rather than gatekeepers, reflecting a broader maturation of the model.

From Service Providers to Capability Owners

Perhaps the most important shift is how responsibility is defined. Platform teams are no longer service providers responding to requests. They are capability owners accountable for adoption, reliability, and long-term evolution.

This redistribution of responsibility allows DevOps concerns to be embedded into systems rather than centralized in a single team. Product teams regain autonomy. Platform teams focus on leverage. The organization becomes easier to scale because delivery no longer depends on coordination through a single point.

By replacing centralized DevOps teams with platform teams, organizations move from reactive support to intentional enablement — a necessary step as complexity continues to grow.

New Metrics for Modern Engineering Organizations

As organizations adopt internal developer platforms and platform-led operating models, one reality becomes unavoidable: traditional DevOps metrics are no longer sufficient on their own.

Deployment frequency, lead time, and mean time to recovery still matter. But they no longer tell the full story. In platform-centric environments, many of the most important outcomes are indirect. They surface in how teams experience the system, how easily they can ship, and how consistently good practices are applied across the organization.

This shift forces engineering leaders to rethink what “performance” actually means.

Why Traditional DevOps Metrics Can Fall Short

Classic DevOps metrics were designed to measure flow through pipelines. They work well when delivery paths are relatively uniform and infrastructure concerns are tightly coupled to individual teams.

In platform-led organizations, however, teams increasingly consume shared capabilities rather than assembling delivery workflows themselves. Reliability, security, and compliance are embedded into platforms by design. As a result, success is not always visible in a single deployment event.

Organizations that rely only on traditional metrics often miss early signals of whether their platform investments are actually improving outcomes or simply shifting complexity elsewhere.

Developer Experience as a Leading Indicator

One of the clearest changes in 2025 is the elevation of developer experience from a soft concern to a leading performance indicator. This does not mean measuring satisfaction in isolation. It means tracking concrete signals that reflect how easy it is for teams to do the right thing.

Metrics such as time to first deploy, onboarding duration, platform adoption rates, and the frequency of manual interventions offer early insight into whether platforms are reducing cognitive load or adding friction. Industry analysis in 2025 increasingly points to these indicators as more predictive of long-term performance than raw delivery throughput alone, as outlined in Platform Engineering Trends in 2025.

When developer experience improves, downstream outcomes such as delivery speed, stability, and consistency tend to improve as well.

Measuring Adoption, Not Just Usage

Another important shift is the move from measuring usage to measuring adoption. Usage can be mandated. Adoption must be earned.

Healthy platforms show voluntary uptake across teams. Developers choose paved paths because they are faster and safer, not because alternatives are blocked. Measuring how often teams bypass the platform, request exceptions, or build parallel solutions provides valuable feedback on whether the platform is genuinely enabling or quietly constraining delivery.

This distinction is reflected in real-world data. Recent reports on internal developer portals show that organizations measuring adoption and friction, rather than just activity, gain clearer visibility into where platforms succeed or fail.

Outcomes Over Activity

Ultimately, modern engineering organizations shift their focus from activity to outcomes. The most meaningful signals are not how many pipelines exist, but whether teams can ship reliably without heroics.

Reduced incident frequency, faster recovery, lower onboarding costs, and improved consistency across teams are all indicators that the operating model is working. These outcomes are harder to attribute to individual changes, but they are the clearest signs of sustainable scale.

Metrics as a Design Tool

In mature organizations, metrics do more than report performance. They shape behavior. What leaders choose to measure influences how teams design systems and workflows.

By aligning metrics with platform goals, organizations reinforce the idea that platforms exist to enable teams rather than control them. This closes the loop from culture to structure to outcomes — and ensures that platform engineering remains a means to an end, not an end in itself.

What Platform Engineering Really Changes in 2026

The rise of internal developer platforms is not a tooling cycle or a DevOps rebrand. It reflects a deeper realization that modern software organizations cannot scale through coordination alone. As systems, teams, and constraints multiply, speed and reliability depend less on effort and more on design.

Across the five shifts explored in this guide, a consistent pattern emerges. Organizations move from culture to structure, from shared responsibility to explicit ownership, and from manual enablement to platforms that encode best practices by default. What changes is not just how software is delivered, but how responsibility, autonomy, and governance are balanced.

Platform engineering sits at the center of that transformation. Not as a replacement for DevOps values, but as the operating model that allows those values to survive contact with scale. By treating enablement as a product and platforms as long-lived capabilities, organizations reduce cognitive load, remove hidden dependencies, and make good outcomes repeatable.

For engineering leaders, the question in 2026 is no longer whether internal platforms will exist, but whether they will be intentional or accidental. The difference shows up in adoption, resilience, and the ability to evolve without constant rework. Teams that design for scale early gain leverage. Teams that delay often inherit complexity they did not choose.

The organizations that succeed over the next few years will be those that recognize platform engineering for what it is: not an infrastructure decision, but a strategic one.